Sound of the Genuine

Sound of the Genuine

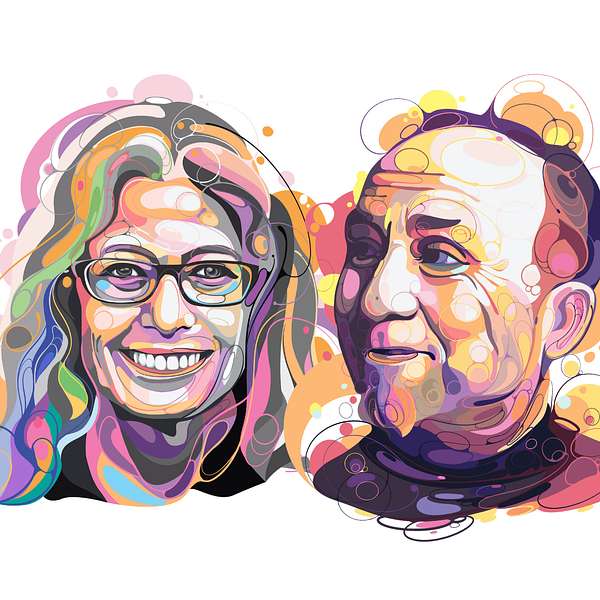

Ched Myers & Elaine Enns: Solidarity and Justice Making

This week Dr. Patrick Reyes sits down for a conversation with Ched Myers and Elaine Enns. Each talks about their radically different upbringings and how their peacemaking and restorative justice work led to their chance meeting. Ched and Elaine have spent the past 25 years at the helm of the Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries, whose motto is “Revisioning the intersection of Word and world. Animating communities of discipleship and justice.”

Ched, an ecumenical activist theologian, is a well-known educator, writer, teacher, and organizer committed to animating and nurturing church renewal and radical discipleship and supporting faith-based movements for peace and justice.

Elaine, a Canadian Mennonite, is an educator, writer, facilitator, and trainer in conflict transformation. She focuses on how restorative justice applies to historical violations, including intergenerational trauma and healing.

Their latest book, Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization, and other publications are available at Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries.

Portrait Illustration by: Triyas

Music by: @siryalibeats

Rate, review, and subscribe to Sound of the Genuine on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Patrick: What's going on? It is Dr. Patrick Reyes here, the host of the Sound of the Genuine, the Forum for Theological Exploration’s podcast on finding meaning and purpose. And today I have some mentors and friends and colleagues from California, from the Homeland! Ched Myers and Elaine Enns who you may know from Bartimaeus Ministries. They are also authors of an incredible book, Healing Haunted Histories. It's a must read. And of course, when you go onto their website, they have a bunch of other reading and resources that you should check out, but this book is the heart of our conversation today. How do we know who we are? How do we heal our ancestral pains? How do we live into those calls and those wildest dreams of our ancestors? I'm so glad you get to hear from Ched and Elaine on the Sound of the Genuine.

All right, Ched and Elaine, I am glad that you have said yes to coming on the Sound of the Genuine. I've gotten to know you over the last seven years or so, but I'm curious. Take me back to your beginnings, your genesis. Tell me about growing up. Who were the people, the stories that were influential in your lives?

Elaine: Thank you, Patrick. We are very glad to be a part of this and glad to have known you for these many years and put our shoulder against the same struggle in some cases. So really glad.

Ched: And thanks to the FTE team that's making the magic happen behind the curtain. We are beaming to you from the Ventura River Watershed in southern California. This is Chumash Territory, unseated/untreatied. We've been impressed Patrick with this podcast and we really do appreciate the spirit of affirmation and inquiry that you curate, having watched you work with groups many times in the past, especially at the Proctor Institute freedom Seminary.

We're maybe not your usual clientele since neither of us are clergy, nor are we professional academics – more(so) folks trying to work more at the intersections. But we're really happy to be included in the circle here.

Elaine: It is a good time to talk about what has shaped us. So thank you for that gift of being able to think through this story and all that I carry in my bones. And so I was born and raised in a tight-knit Mennonite community in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. They are part of the radical wing of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. And they believed in pacifism.

Mennonites were pioneers of the radical idea of separation of church and state. And for this, they were heavily persecuted and driven all over Europe. They were often killed. They were not allowed to own property. They were pushed onto marginal lands. And so as a community, they moved all over the place around Europe and Euro Asia. My people moved from the Netherlands to Prussia and then to Ukraine and Russia. There they lived for about 150 years and were allowed to be in semi-autonomous communities and they became very successful agriculturalists. And they suffered severe violence during the Russian Revolution and civil war because of the huge economic and social disparities.

I was born into a tradition identity that spoke in terms of we - we as a Mennonite people, and lived into this real sense of extended community. And most of the social space was Mennonite space. My grandparents and parents worked hard on preserving the German language and preserving community. And we as a community had a history and social infrastructure and institutions like universities and grade schools, businesses and churches, and our faith. So we could travel within a Mennonite community that I essentially did until I met Ched, and had this strong sense of who I was as a Mennonite. And then church was so central to our life.

My parents were co-founders of one of the first English speaking Mennonite churches in Saskatoon. And I know this is similar to other folks, but I went to church five times a week. And so, that is a huge piece of shaping who I was. A huge mark on my family and this community was that all four of my grandparents and along with 20,000 other Mennonites, came as refugees from Ukraine and Russia after the Russian Revolution and civil war.

And many of these folks, like about 7,000 landed in Saskatchewan in the 1920s. Huge impact on actually all of the Canadian prairies. But this experience drastically shaped my parents and the whole community. But as adults, my parents were heavily involved in refugee resettlement work themselves. And so all of my growing up years there were refugees from all around the world gathering at our kitchen table.

But I do wanna start with these stories. I have worked in the field of restorative justice since 1989 as a practitioner and trainer. I owe the calling into this vocation to my family and my faith community. They nurtured me onto this path in ways I am only now beginning to understand. The following braids of personal narrative offers three snapshots of my childhood. Three vignettes involving young teenage girls.

Osterwick, Ukraine 1918. 100 years ago as I write this, my maternal grandma, Margreta Schultz, then 14, survived a two-week home invasion in her village. This was just one episode in a continuous climate of violence, plundering, rape, and killing, endured by Mennonites and other German speakers during the Russian Revolution and civil war.

Margreta's mother Anna, trying to respond to violence with courage and compassion, bandaged the wounds of and fed rough and demanding peasant soldiers. It is difficult to believe that these females escaped sexual violence as assumed by the family's stories passed down. During those days and nights of terror. Margreta experienced severe trauma, yet she also witnessed her mother's profound embodiment of her tradition of non-resistance. Anna, my great-grandmother's response to the home invasion may have warded off the worst. Some months later, her sister and three other relatives were brutally murdered in their home.

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 1980. As a child, I knew something horrible had happened to my grandparents, each of whom came to Saskatchewan as refugees. I wanted to understand more. So at age 13, I interviewed Grandma Margreta. I recall that she spoke at length of the beauty and abundance her family had enjoyed during her childhood years in Osterwick. But as her account approached her teenage years, she began to weep and could not continue. Seeing her cry left an indelible impression, planting in me seeds of both curiosity and trepidation.

Winnipeg, Manitoba, 1988, in my final year of college, I volunteered with a Big Sister's, little Sister's program in Manitoba, and I was paired with a 13 year-old Cree girl who had just been released from juvenile detention after three years. She was living in a group home, pregnant for the second time with twins, and her “crimes” had been sniffing glue, stealing food and clothes, and getting into fights. Behaviors I now understand as reactions to a racist colonial system that did not meet her basic human needs. Despite my lack of race or economic analysis at the time, she helped me see that the criminal justice system was unable to address the injustices she faced. She described to me the pain of being forced to give up her first child and of not knowing where he was. She vowed she would not give up her twins and wanted them raised on her reserve by an Indian family.

On the cusp of adulthood myself, this encounter raised a new set of questions about how her ancestors had been displaced by mine on the Canadian prairies. It was my first tutorial in the hard truths of colonization and planted seeds of disillusionment with my comfortable middle-class white world.

So this experience with my little sister helped me see how broken the criminal justice system was, and I really wanted to find people and places that were pushing against this and experimenting with alternatives, surely to the criminal justice system, but also where I could learn more about the stories that I carry in my bones.

Ched: Unlike Elaine, I come from a highly fractured family, perhaps more typical of American assimilation and migration. My father was a survivor of two wars. He was half Chicano but had a non-Hispanic surname so he could pass and he did. He came from a very working poor family but married a very WASPish upper middle-class woman.And that was, I think, hard for them. This was during the second World War.

Elaine can trace her genealogy almost back to the 16th century. We can't get past the 1840s. But what I do know is that my dad's great-grandfather came from the Azore Islands, off of Portugal. Driven out by the unrest of the late 1840s, he came to Mexico by boat and then I think probably heard about the first murmurings of the gold rush. And so came up to Sonora in the Sierra Foothills in California. And he didn't make it as a miner. Most people didn't but he did marry a Californio that is a woman who was part of California when it was part of Mexico. Her name was Inez Unez Nunez. What a cool name.

They settled in Sonora. Sonora was at that time a largely Mexican mining camp. Most of the mining camps were segregated by language race and culture in the early years of the Gold Rush. They had a family and then eventually migrated out.

My dad was born in San Francisco. My mom was born in Seattle, but raised in San Francisco. I have five generations of being in California, but very little to show for it materially. Nevertheless he made it in the white world. He became a business executive. Both my mom and dad graduated from UC Berkeley as I later did. The trauma of war ran right through our household. As I said, my dad was drafted into World War II and then called up again during the Korean War to earn his way through college. He'd been part of the officer corp.

He really came back from Korea damaged, but of course like almost every one of his generation, he never talked about the action that he had seen. And then as I'm growing up in suburban Los Angeles my older brother is drafted into the Vietnam War. And he almost immediately went AWOL.

It was kind of a heady time. I went to my first anti-war march, became a vegetarian in my early teens. It was a late sixties, an exciting and fraught time. My dad's raza was very much submerged. We spoke a little Spanish at the table.

He would listen to the Dodger baseball games in Spanish. He was an only child. His family and tradition had been pretty much wiped out so we were mostly submerged in my mom's family who lived nearby. And I never knew my paternal grandfather.

So that asymmetry in our family system had a real psychic footprint. A lot of alienation. So I got outta Dodge as soon as I could. I was an exchange student to Scandinavia for a year and had to learn a language from scratch in a very different part of the world. But I also saw the war, this was 1972, the bombing of Cambodia, from an unfiltered media of Scandinavia.

I was living with a working class family of two survivors of the Norwegian resistance to the Nazis who were both invalids. And that was in a little gritty little post-industrial town in Norway. In every way - environmentally, socially, this was me being launched out of the bubble of suburban Southern California life.

I was also unchurched, unlike Elaine. We didn't have an experience of church or church community. Upon coming back from my travels, I was caught up in the early Jesus movement of the early seventies. And that exposure to the gospel gave me a real sense of existential relief from my alienation, but left me politically orphaned.

So off I went to college at UC Berkeley, and there I was exposed to a radical, more radical form of Christianity, which helped me connect the dots. And that's where adulthood began for me. But Elaine, you left off at you also leaving home and coming to California to do restorative justice work?

Elaine: Back then we called it VORP: Victim Offender Reconciliation Program. Now we're not as lofty in terms of the reconciliation part. We talk about it in terms of victim offender dialogue or victim offender facilitation. But in 1989, I left Saskatoon Saskatchewan on a Mennonite voluntary service assignment with this VORP program and I came to Fresno, California. I was immediately thrown into the work of facilitating these victim-offender dialogues, primarily with juveniles involved in mostly property offenses. Sometimes assaults as well. We'd help them make these agreements of restitution and then I would go around to their homes and talk about how they can possibly start making these payments.

And really got to be in the community and meeting with young kids that I immediately recognized the experience I had with my little sister in Winnipeg. Here were these children caught up in the same rotten system that was not helping them first accept responsibility and take true responsibility of what they have done. And secondly, or equally important - why is this happening with all these beautiful children? And of course you well know it most of the kids were kids of color. And I'll never forget, early, early on, five Latino boys pleaded guilty to something they didn't do. What is happening here? You can't work that close with the criminal justice system and with the family so heavily impacted without seeing the cracks and holes in it.

So in the next decades, I sought a different set of mentors, those who had experienced systemic injustice and made the arduous journey from either victim or offender to survivor to healer. And that is just around the time that I met Ched.

Ched: 1976 was a really important year in my journey. I was 21. It was the year of the bicentennial, and we were just recovering from the Vietnam War and the Nixon administration. Someone came to me in my dorm room and said, there's somebody coming to town who's gonna do a weekend retreat. And there I met Ladon Sheetz.

Ladon Sheetz was from West Texas. He was a white guy. He'd been raised by a hard scrabble, Churches of Christ background. Been in the Air Force, was part of the first great computer boom of the 1960s. Worked for IBM, was living large, high-flying, jet-setting. And then he, through YoungLife, met Clarence Jordan, the radical Baptist preacher from South Georgia, who was the founder of Koinonia Farms and who did amazing interracial justice work in the teeth of Klan terror and community opposition down in Americas, Georgia. Ladon's life was turned around by meeting this preacher, scholar, activist.

He ended up leaving his job, giving away his wealth and going to Koinonia to serve the sharecropping community. I met him in 1976 and he had the same impact on me that Clarence had on him. He preached the whole gospel. And I, in my nascent Christian faith, I was like, oh, that's what I signed up for.

So I dropped outta school, hitchhiked across the country, and joined Ladon and others at a little radical Christian community called Jonah House in inner city Baltimore. Jonah House was committed to peacemaking. It had been founded by Phil Berrigan and Liz McAllister, who were Catholic radicals from the 1960s. And I was so deeply drawn to their holistic way of life, deep commitments to community, to nonviolence, to justice. After doing an internship there, came back to the West coast and we started our own intentional community in a working-class black community in West Berkeley.

We grew to four households, some 25 people spanning the generations. We were committed to simple living, to peacemaking, to neighborhood relationships. Ran a little community church at an old abandoned Episcopal Mission church. I managed to finally graduate from college and start in a New Testament studies degree at the Graduate Theological Union. I was doing all this part-time while organizing and doing community work. And we supported ourselves by painting houses. And some of the gigs we got - the places to paint were GTU buildings. And so I had the really interesting and revealing experience of on one day I'd be up on Holy Hill, as we call the GTU in those days, with my little briefcase going to class and I'd be recognized. The next day I'd be up there in my coveralls up on a scaffold or a ladder painting the same building and being invisible. And that was just a really good tutorial in class gulfs and bias.

In 1980, my peacemaking vocation was really rocked. I went to a Pan Pacific Indigenous sovereignty and anti-militarism conference that were attended by indigenous activists from all around the Pacific Basin. And there I was really confronted with the white middle classness of the First World Peace Movement. This is now the beginning of the eighties, the Reagan era, and the peace movement was preoccupied with the, what we might call the eschatological threat of nuclear war. Right?

Height of the Cold War. ‘What might happen if a 10 megaton bomb exploded over Chicago,’ kind of thing. Whereas Indigenous people, whether it was Navajos talking about uranium being mined on their land, or Pacific Islanders talking about the nuclear waste dumped in the Marianna's trench off their islands, right…So from the beginning to the end of the nuclear cycle. And especially folks who had had bombs tested in their islands and were suffering the effects of radiation poisoning. These people had already experienced being bombed. They had already experienced the realities of military colonialism and so there's nothing eschatological about it.

So that was just a complete rearranging…my first exposure to the decolonial critique. So I came back all on fire for this new way of coming at these heartfelt issues. And found myself kicked outta the peace movement. People just did not want to hear about this stuff. So I just said, all right. we'll just work in a small office in San Francisco doing solidarity work with indigenous communities in the Pacific, some of the most overlooked peoples in the world. one of my mentors in this work was Darlene Kaju. Darlene was born in the Marshall Islands. She Was four years old when the US tested nuclear weapons on Bikini Atoll. fallout blew over and fell on Regelap where she was. Of course, it was radioactive ash.

Darlene grew up to be this amazing woman, this activist who was an advocate for victims of radiation, for the displacement of Marshallese by US military bases, for the injustices of being second class citizens in their own homeland. She was one of the people who I got to be mentored by.

Darlene mentored a whole generation of Pacific Island activists. And Darlene passed in the mid-nineties of breast cancer as a result of her own exposure to radiation. I didn't have an organic community like Elaine did, but the community of people in struggle who welcomed me in and who mentored me and really adopted me was a huge impact in my life. Anyway, I ended up spending some time out in the Pacific Islands and on the Pacific Rim organizing for sovereignty and demilitarization. At that time in the 1980s, of course, the foreign policy issue was the Central American wars, both covert and overt. Our community was deeply involved in that work.

But those were the times. But there were also times for me as a young activist of personal loss and failures relationally. Through all these transformations, I clung to my studies in the New Testament Deeply influenced by the Liberation Theology that was trickling up from Latin America and elsewhere. I studied political hermeneutics and sociological exegesis at the GTU at a time when very few North American seminaries were oriented to that kind of material. So I was kind of on the margins there. Got fired by a couple of professors for the work that I was doing. So I left the seminary, decided not to go on to PhD studies and become an academic. I just thought that the academy was too insular and I felt like the energy for me was in social movements. So I began working full-time with the American Friends Service Committee, pivoting from international solidarity work to domestic justice issues under the tutelage of some of the finest BIPOC veteran activists of that era in the late eighties, early nineties. My supervisor, Tony Henry of Blessed Memory, was this veteran activist and we worked on all kinds of local issues, housing rights and gang stuff in Northwest Pasadena. And we were up late one night finishing up a CDBG block grant.

And I said, “so Tony did you ever know Dr. King?” This is somebody I'd worked with for five years. And he says, “Yeah. I was at the Lorraine Motel on April 4th, 1968 as part of the Poor People's Campaign Organizing Committee. We were waiting to have a meeting with Dr. King when he was assassinated.” And my jaw just hit the floor. Here I'd been working with this guy for all this time and he had never mentioned this. In looking back on that, I realized that in equal parts it was probably part of the trauma for him. But it was also that we don't do a very good job in our social movements, telling our own stories and curating those sacred stories of struggle because we're always onto the next thing, right?

There's always something else pressing and it's about now. I really appreciate how that man just was another level of deepening for me. And I appreciate that he didn't wear it on his sleeve, right? He just was about the work.

In 1991 the first Gulf War ran back through my life and my father passed away right after we had a big argument over that war. And in 1992 was the second Los Angeles uprising. A second time I'd seen my city burn. And these were really apocalyptic events in the true sense of that term, unmasking the realities of life in the American Empire.

those days of living and working in East Los Angeles, we worked very closely with the early homeboy industries, doing a lot of immigrant rights at the US Mexico border. The Posada sin Fronteras that still takes place at the US Mexico border in San Diego each year we started in the, early nineties as an attempt to do public theater using that great tradition. but because I felt like we weren't doing a good story as storytelling as movement people, I decided that I wanted to go more into kind of the work that, that you do, Patrick, which is helping people curate their stories of struggle and doing that, in my case, through the work of animating scripture to open up our imaginations to talk about justice work.

By the end of the end of that decade, I had left the FSC (Friends Service Committee) and was traveling the country doing popular education around social issues and reading scripture with folks. And lo and behold that took me to Fresno in 1997, and there I met this one.

Elaine: And we are so grateful. We feel like it, it was kind of impossible, our meeting. There was a very slim window there. We were living and working in incredibly different camps. I was teaching at Fresno Pacific University and doing restorative justice and other facilitation work. Our Shalom Covenant group, it was a student group, was hosting the Intercollegiate Peace Fellowship conference. Mennonite colleges in North America had an annual conference every two years. One of the students who actually struggled with me, because I was not married yet and I was feeling okay with that. I was 29 and I hadn't met someone that I could commit my life to. She, this young student was of the opinion, and I'm sure well, maybe you're not familiar, but in Mennonite colleges ring by spring or your money back. She was not believing me at all. She is the beautiful young woman who invited Ched to be the keynote speaker and I am grateful to her. So Ched was the keynote speaker, I was leading some workshops, and again, it was focused on peace. And we were immediately interested in how each other was talking about the work we did.

We agreed on our analysis of violence but were curious about how each other did our work in these different spheres of peacemaking. Ched was mostly working in non-violent, direct action camp. I was in this mediation and facilitation camp and each of us were seeing the holes in our practices. But also recognizing that these two practices of peacemaking were skeptical and wary of each other. I think we should talk a little bit like about the holes.

So not only victim-offender dialogue, but I was doing other types of mediation work too. And in this mediation work for sure, there is an emphasis on process and on not taking sides. So we have a tendency to focus then on interpersonal dynamics to the exclusion of structural ones. And so in the victim offender dialogue, folks would want to just focus on the incident and ignore the social context and the larger historical context and deal only with the presenting individual violation.

And again, this was in the early nineties. Facilitators did not receive any anti-racism training so were unequipped to even see when those issues came up in the facilitated conversation. I just wanna say in 1998, I had an opportunity to teach at the University of Winnipeg. And there I met indigenous leaders who helped to further open my eyes to the realities of systemic racism and the blind spots in the contemporary restorative justice movement

Ched: And in non-violent direct action we see the need to disrupt, to unsettle, but we're not too good at actually making peace and overcoming conflict. And that was the major problem there. So our first date was a conversation about how to reintegrate these two branches of the great peacemaking tree and that took us to a Christian Peacemaker Teams conference in Indiana.

[00:29:49] Elaine: Yeah. 1998 probably about a year after we had met there was this wonderful gathering at a farm in Indiana, and there Ched and I led a workshop on these different branches of the same peacemaking tree, arguing that these two traditions of non-violent action and facilitation or dialogue, though they are estranged, we're in fact relatives of the same tree. And that we need everyone working in the practices that they feel called to, but also recognize when they need each other's skillset.

Again, mediators thinking, I can mediate anything and really almost feeling triumphant in that are unable to see where there are such huge injustices or violations, that mediation is not the strategy that needs to enter this situation - then we need to turn to our practitioners of non-violent direct action. And non-violent direct action folks need to recognize when there is an opportunity to bring people together in a conversation. It can be heated, it can be in incredibly intense, but there may be places where we can come together and move on that.

Ched: Those were the seeds of our 2009 Ambassadors of Reconciliation volumes, where we talk more about how to integrate what we called full spectrum peacemaking. So what you're hearing us narrate really up until the end of the last century, is the reason why, in 1998 we started Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministers named after the Poor Man who just wanted to see. And who Jesus heals in the Gospel of Mark. That story animated me when I was in my early twenties and it continues to animate us because it speaks to... you kinda see in our narrative, these layers of shedding spiritual and social and political blindness about how the world really is. As white folks of relative privilege who have tried to make choices of solidarity and justice making, you know, it's just a constant learning and shedding process, shedding denial, shedding blindness in order to see the world the way it actually is. Particularly from the perspective of marginalized folk. But also to hold the vision of how the world could be according to God's dream of justice.

So that brought us into our current work with Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries. We've been running that for 25 years. And that in many ways was reanimated in the late nineties by our meeting of Nelson and Joyce Johnson and the Beloved Community Center folks of Greensboro.

Elaine: I am just so grateful to Joyce and Nelson Johnson. I don't know if listeners are familiar with the story of the Greensboro massacre. In 1979, Nelson and Joyce were organizing in the community trying to bring white and black workers of textile mills together to push for better wages, better working conditions in those mills.

But they were doing this black and white organizing that was pushing, of course, against white supremacy there in Greensboro. Ku Klux Klan members collaborated with the police on November 3rd, 1979, and they drove to the site of the beginning of this labor parade going through the streets of Greensboro. They shot into that labor parade killing five people and wounding 10 others. Nelson was cited for starting a riot and arrested. These friends and elders and mentors, their work of bringing a Greensboro truth and community reconciliation process to the US soil for the first time.

An extraordinary labor of uncovering the stories of the land, telling the truth of what happened on that day and the history that led to that day. Inviting a national commission - I think it was seven commissioners that listened to hundreds of hours of testimony about the impact of this day of November 3rd, but also the history that led up and what had happened since. An extraordinary experiment in a public restorative justice experience.

And one of the things in getting to just be around the table with Nelson and Joyce, I was interviewing him again for the Ambassador's book and I asked him “Where does your courage and conviction come from?”

And Nelson looked me straight in the eye and said, “When I was born, the people who held me were enslaved people or children of enslaved people, and I need to bear witness to that.” That grabbed me in terms of, what do I need to bear witness to? What do I carry in my bones? What is the toxicity of white-ness that I carry, that I need to do work on?

Ched: So as refugees from academia that as people trying to do serious theological work outside the academy we teamed up with the beloved community center and colleagues from around the country to begin an experiment in alternative social movement building and theological reflection, which we called Word and World.

And between 2001 and 2010, we held seven schools in seven cities. Each city told the story of a social movement in that place narrated by people who had actually been part of that history and then reflected on current issues and did bible study and worship together. It was an extraordinary experience of integrating the seminary, the sanctuary, the streets, and the soil.

We picked that work up because it was very difficult to sustain as a traveling circus around the country on a shoestring. So we then launched our institute 15 years ago here, which we do annually in the same spirit. So over the last almost quarter century now through BCM, we've been trying to express that capacity building through organizing and advocacy through education, and increasingly through mentoring. You wanna talk a little bit about some of the ways in which we did mentoring, and then the new chapter that you started in 2010?

Elaine: Early on, we got involved with the Abundant Table Farm project, which is a wonderful expression here of how do we grow food in a responsible way? How do we honor the lives and the work of the farmers that are growing our food? And how do we yeah, support that effort around food justice? And so we got involved with them early on 2008. They are BIPOC led Collective where Farm Worker Justice is at the center.

And through that realized, we so felt called to start working with young folk and supporting the incredible work they were doing and the struggles, how they saw them. And so really, we prayed about that and talked about, you know, if we are not going to have our own biological children, what does it look like to parent in a different way – to be involved and support young people that are doing great work? What does that look like? So that really launched us and we’ve continued to do that for 20-some years.

Ched: We noticed that at the turn of the millennium there was just young kids streaming out of the big box evangelical churches, trying to have more meaningful, holistic social justice orientation, but not knowing where to turn. And we really wanted to make ourselves available to help midwife them into the same stream that we'd been midwifed into over the previous 25 years. So that's been an important part of our work. Last thing we wanna talk about, we know we've gone way past your normal time, but let's just talk a little bit about the seeds of the current work with your trip to the Ukraine.

Elaine: Yes. I had the incredible gift of going back to the place where my grandparents came from. So in 2010 I went on this Mennonite Heritage Cruise. cuz we were on this tiny little boat up the Dnipro River. and friends. The war that is raging there now is raging right through the communities that I saw and the beautiful people that I met.

Ched: A hundred years after.

[Elaine: A hundred years after.

Ched: After your ancestors.

Elaine: Yeah. So we went up the Dnipro River and got to stop in the communities. I actually got to go to the home where my grandmother and great-grandmother were responding to the soldiers that came and that house had a fire the previous year and so it had been abandoned. And my sister and I were there with a Ukrainian guide and she said I wouldn't go in there, there are dogs. But, you know, we just decided we're never gonna get here again. I have to go in that building. We slid under the fence in the rain, got all muddy, but we walked into that house and I stretched up the rickety stairs that were broken and just lay there and looked into that room where my great-grandmother would have fed and clothed those soldiers. And imagined my grandmother in the attic above peering through and watching what was happening in there.

Being able to walk that land feel the stories that are carried there, and then also learning more about the first displacement. And I know there are many, but the Mennonites that came to Ukraine and Russia, they displaced the Nogai, the indigenous people of that place. And then they came to Saskatchewan and displaced Cree. And the stories of wealth disparity and complicated layers…all of this culminated or encouraged me to do a Doctor of Ministry degree, which gave me the opportunity to explore historical violations of other people and how my family and community was caught up in a history that needed healing.

Ched: That's kind of a coming in full circle for you for sure, to your legacy. And also for me, the Healing Haunted Histories project that we started writing just prior to the pandemic and published last year was a full circle for me because it was coming back around to the indigenous issues that rearranged me almost 45 years ago.

This has been a circle of journey to ever deeper discipleship. And we've appreciated FTE's accompaniment and support particularly in the last 10 years. And we've also appreciated working with you Patrick, with the Proctor Institute of the Children's Defense Fund. Which has really been a great space for this kind of working at the intersection of seminary, sanctuary streets and soil on the holy ground of Haley Farm. We've done a lot of other work around sabbath economics and watershed discipleship, but why don't you close it maybe with a word about the struggle on your family homelands up in Saskatchewan.

Elaine: When I was a child again, I heard whisperings of what had happened to our people. But what happened? First Mennonite settlers got to Saskatchewan in the late 1890s. My people didn't come until the 1920s, but there were three waves of Mennonite migrations that impacted Saskatchewan. In 1890s, boy, it is beautiful land there in Saskatchewan and Mennonites kept telling their co-religionists come…It is beautiful up here. So the land that had been set aside for Mennonite reserves, that's what they actually called them back then, was not enough for the growing Mennonite community. 1876 was when Treaty 6 was signed in Saskatchewan. At that point it was mostly Cree territory.

Cree also displaced Blackfoot a number of generations earlier. Treaty 6 covers a huge swath of land. Most of Southern Saskatchewan also swings into Alberta and Manitoba. There was a band called The Young Chipeewayan. Their Chief, Young Chipeewayan signed Treaty Six in 1876 for a small, 30-mile square tract of land for his people to survive.

The buffalo were disappearing because of the slaughter that white hunters were a part of. There was no food. And so Chief Young Chipeewayan took his band and went south to find food. The Canadian government took this as a sign that the Young Chipeewayan had abandoned and never claimed their allotment of land there.

Reserve is the language that is used in Canada. So without consultation or compensation, gave this land to new Mennonite settlers. And then later, Lutheran settlers. So Mennonites lived on top of this land. And then the 1920s, Mennonites also came in and some of them took up in that land. And so part of what I've been wrestling with is two traumatized communities living side by side, in isolation from each other until very recently when Cree activism began pushing for their story to be heard, and there was an openness in the Mennonite community.

So in 1976, this history all comes bubbling out. It's the hundred-year anniversary of the signing of Treaty 6 and some of the government officials wanna give a medal to one of the Chiefs. And the Chief says, I don't want your medal. This has been a hundred years of broken promises and gave the litany of what had not been honored in these treaties. There were some Young Chipeewayan in the crowd saying, yeah our land is somewhere around here. Let's go look at it and talk to those farmers.

That day led to extreme Mennonite discomfort and in some parts denial of the land that we were on. But it also awakened in others [that] there has been a huge mis-justice and we have benefited from living on this land for 150 years or a hundred years. We need to respond and do something about this.

And this is a story that we narrate in Healing Haunted Histories. And it is small steps of settler communities trying to figure out how to support Indigenous communities in how they want to move towards justice. And beautiful things have happened even since the publication of the book. And just quickly to say, Young Chipeewayan were not federally recognized band. They did not own land. They were not federally recognized by the government. Just when we were up in Saskatchewan this past August, the Young Chipeewayan have qualified for compensation, meaning that they are on their way to be a federally recognized band and to receive compensation for the land that was stolen from them.

So a very exciting chapter in what is happening between Mennonite, Lutheran and Young Chipeewayan in Saskatchewan.

Ched: So in many ways that little episode at Stoney Knoll in Saskatchewan, we realized in researching this, that this was a microcosm of the entire history of Turtle Island and settler Indigenous relations. And ghosts that continue to rise up from unresolved legacies and unsettle the landscapes, so that we always have new opportunities to try to make repair and make things right.

And just as Stoney Knoll was a microcosom of injustice, so now it is becoming a small but significant example of restorative and repairative justice by these historically traumatized settlers and traumatized indigenous people coming together and saying, how do we make things right and how do we build community with each other?

And how do we forge land justice? This is the kind of work that lies now at the heart of our efforts. And that reminds us that our journey away from blindness and denial toward a deeper discipleship is ongoing even as we now start to get a little long in the tooth ourselves. So, we are so, so grateful to have this opportunity to be long winded with you.

Patrick: I wanna say thank you for my opportunity to listen to these stories. Ched and Elaine, one of the things I want to…you picked up on this a little bit, Ched, as you talked about the social movements - our inability to narrate those histories and we want to get to the next thing. And I hear a little bit of this in the story, which will lead me to this last question I hope you both answer, and it's this idea that you have just narrated about: trauma, refugees, cultural loss - Ched in your story around how your lineage is this cultural loss, and the pain and the trauma that causes for the next generation…Elders who have come, folks who were there at Dr. King's murder. Elaine, I'm thinking of this reconciliation on the land that goes back generations for people who probably don't feel it in their bones and environmental loss. I mean, these are things…everything you have narrated are heartbreaking. It destroys our soul, our planet, our communities, and the fact that you've narrated this quickly, I'm gonna say not long-winded, but this quickly and not made space for the deep grief that comes with this.

I am curious, you know, I've asked everyone on this, how do you live this call? Where does it come from? Does it come from some sort of inner self that you want to see? If it's Bartimaus, like you feel this call to see, bear witness to the world, does that call come internally? Does it come from the divine?

Does it come from community? Does it come from each other? Tell me about where this call and gives us a word for that next generation who's coming behind, who's thinking about doing and living lives of justice as you both have.

Ched: One of my teachers in theology taught me that biography as theology should be at the center of our tradition. The storytelling of lived, embodied individuals and communities is the lesson, I think, probably I've learned more than Elaine. Elaine growing up in this relatively intact ethnic community with a strong tradition of faith. Me from a more assimilated, fractured family. I've learned people talk about chosen family ever since I walked in the door late one night in Baltimore into Jonah house and was welcomed into the arms of Philip Berrigan, this bearer of the tradition of faithful resistance - I knew that I had been adopted into a family of spirit and struggle. Ruby Sales talks about it as a river that's been going on and on through the generations into the deep past of the Exodus and beyond, and we are invited to step into that river. And it's a counterintuitive image because once you step into that river, you're constantly swimming upstream of the imperial story…against this imperial story. But it is this stream and all of us raised in the culture of market capitalism suffer constantly, not only from trauma and loss, but from atomization and alienation and balkanization.

So we don't know each other. The generations don't know each other, the movements don't know each other. And that's why we are constantly being divided and conquered. It’s become very clear to me that the only way to deal with grief, to deal with loss, but also to find joy and find hope, is to constantly remind ourselves that we are not alone. It’s not just up to us. We are part of something that is so much greater than the sum of its parts. That’s the definition of a movement. We usually act as if we are less than the sum of our parts. And so it's that mythos of being what we call small seed church, that ecclesia, that gathering of those striving toward wholeness, toward repair, towards justice, maybe even toward reconciliation. And maybe even toward intimacy with each other across these gulfs, that is the healing I think to realize that kind of adoption. I really think so much of our biblical faith talks about that - being adopted into this family of struggle, of tradition, of covenant, of carrying on, of cloud of witnesses, right? We're just on the cusp now of all Saints and di de Los Martos and we will bring to consciousness all those who have passed.

We've lost some elders in the past year, so dear to me. Norman Gottwald, this beautiful world class scholar and friend. So many people. We've lost Elder Lawrence, Tony Henry, and yet they surround us with their love and they cheer us on. So I think that's how I deal with the grief.

Elaine: Yeah. When I think about again, being raised in such an insular community that gave me lots of gifts, but also lots of wounds, and then busting out of that and meeting people - the Johnsons, like Elizabeth McAllister, like Mercy Davis, like Vincent Harding - folks that are working the edges of their faith traditions, and again, Christian faith. I realized I had more in common with, or drew more strength from their life and witness. And so grateful for the opportunity to be able to stretch across those different divisions and find each other. One of the gifts of being church together is that we get to sing together and we get to play together, and we get to work together and dance together. And research shows that when we do these practices of church together, our cortisol actually comes to higher levels. We need to continue and create these spaces where we do come together and see and play and work, sing, dance, confess – and in doing so, build each other’s courage up.

And that is, that is the things that happen at the Proctor Institute. That's what happens at the Bartimaeus Kinsler Institute, is that we gather as a radical discipleship committee. We see each other, we see the current historical moment as it is. And we don't deny, we don't un-forget the past and all of the work that is needed to do there. And that is where I feel I get my courage, capacity, and conviction in being radical discipleship community together.

Ched: FTE shares this concern. What is the future of our religious communities? And I think we would say if we didn't have a gathering, right, the word ecclesia/church in Greek and synagoga/synagogue in Greek, they just mean gatherings. Gatherings to do important work of sacred storytelling and support and visioning truth telling. If we didn't have these communities, we would need to reinvent them because they're exactly the spaces we need. We just need to re-inhabit them more deeply and robustly. And that's why we like to join our efforts with those of you and others at FTE to help revivify existing gatherings and/or curate new slash old gatherings.

Elaine: I want to add one important piece. The intergenerational gift of church of these gatherings is central. To have the babies dancing and playing with us, to have the teenagers and folks that are working in all the different decades, we need those people. We need to do this work together and honor each other's gifts in the moment.

Patrick: I wanna say thank you for my opportunity to listen to these stories. I mean, the gift that it is to receive them and to be on the listening end of the, it's what family and community is all about. And I'm so grateful that you are in my life and by extension of my family's life and faith communities as well.

I mean, I know thast the world that Carmelita and Asher will inhabit is better because we have met, because of the lives you have lived, and the lives that we're seeding together on this planet. So thank you both for doing this. It really is a gift so I'm deeply grateful.

I want to thank you for listening to the Sound of the Genuine and Ched and Elaine's story. Be sure to check out all of our other resources on fteleaders.org. I want to thank my executive producer, Elsie Barnhart and @siryalibeats for his music. We hope this interview and the many other interviews on the Sound of the Genuine can help you find the Sound of the Genuine in you.